However, it seems the phrase was coined a little early, as now it seems even more ominous. The “Lost Decade” has turned into the “Lost Two Decades”, and many of the same economic problems continue to plague the nation today. The most recent data from Japan’s Cabinet Office pegged Japan’s GDP growth in Q4 of 2015 at -0.3% compared with the previous three months. That’s now two negative quarters out of the four in 2015.

Japan’s Demographic Headwinds

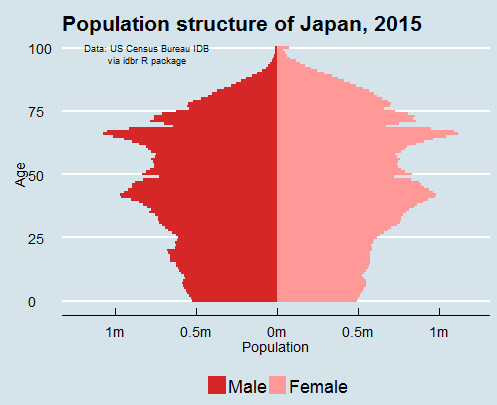

The problem is that the outlook isn’t getting any better with time. Japan is saddled with the most debt of any country, the largest monetary base as a percentage of GDP in the developed world, and the BoJ has now endeavored to go negative with interest rates. In the background, and even more important, is Japan’s lingering demographic crisis. The country’s population is projected to fall from 127 million to 87 million by 2060, at which point more than 40% of the population will be older than 65.

Over the years, there have been many warnings that Japan’s population could begin to contract. However, this problem is now officially here, with the most recent census data showing that the Japanese population shrunk by nearly 1 million people between 2010 and 2015. The working-age population could decline as much as 40% over the next 45 years. This would be coupled with a surge in the people dependent on social services, since Japan has some of the best life expectancy rates in the world. By 2050, there could be just under 1 million Japanese that are 100 years and older in age.

Stopping the Decline

The urgency of Japan’s aging population is not lost on the public. In a recent Pew poll, Japanese respondents were asked if the next generation of children would be better or worse off than their parents. The overwhelming victor was “worse off” with a 72% share of the vote. That’s why the current stated goal of the government is to keep the nation’s population from falling below 100 million by 2060. To do this, Japan is now working on “bold proposals” to find ways to raise the birthrate. The traditionally isolationist Japanese culture is even warming towards the idea of getting new blood through immigration. However, even in meeting this audacious goal, the country’s population will still decline by 27 million people by 2060. It’s also unclear if or when economic growth could turn around, even in the best case scenario.

Turning Japanese

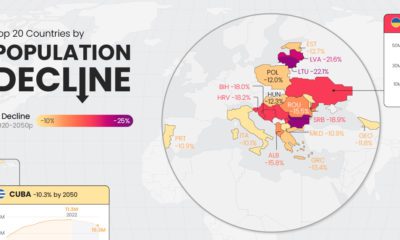

Japan was the first country to experience the cruel cocktail of economic stagnation, shrinking population, spiraling debt, and desperate monetary policy. However, it won’t be the last. Germany has an eerily similar demographic cliff. The U.S. has racked up $8.4 trillion in new debt under the Obama administration. Central banks around the world continue to take unprecedented action. QE, negative rates, the war on cash, and helicopter money are all coming to a country near you. No policy option is sacred anymore. We must watch the Japanese problem closely, because we will need to have better solutions. Original graphic by: Revolutions

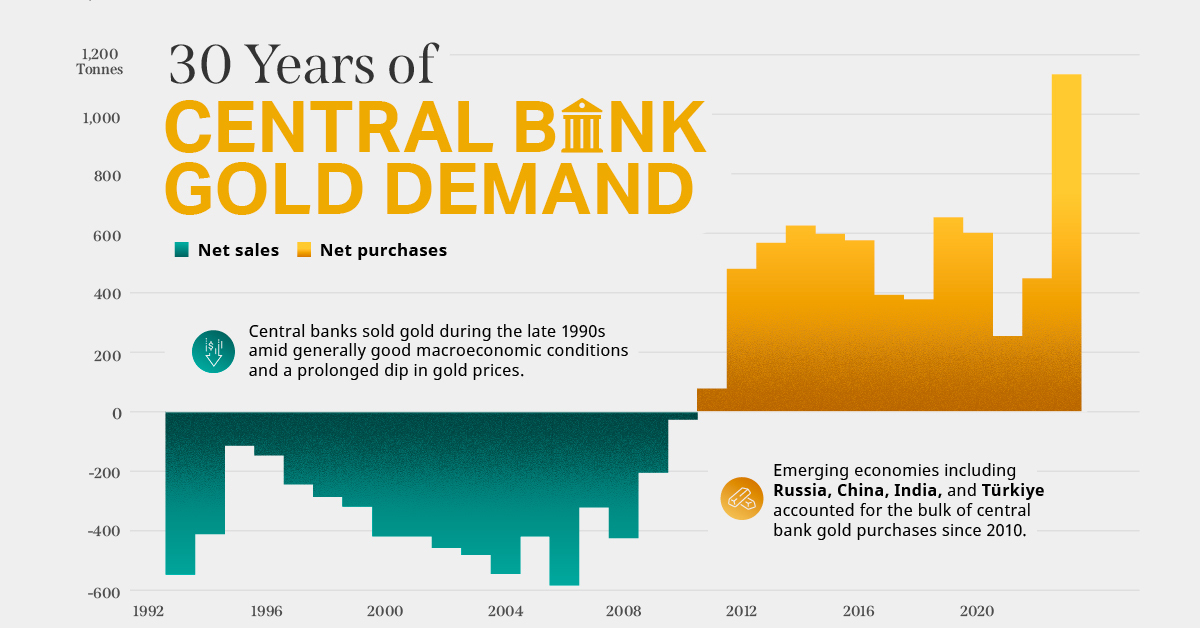

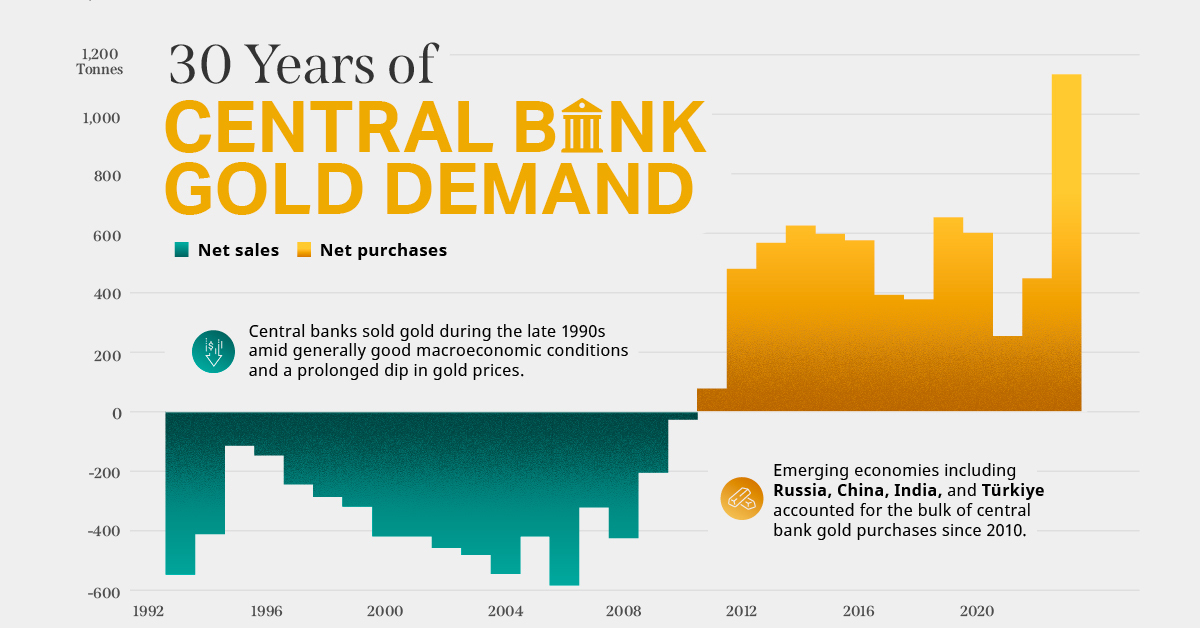

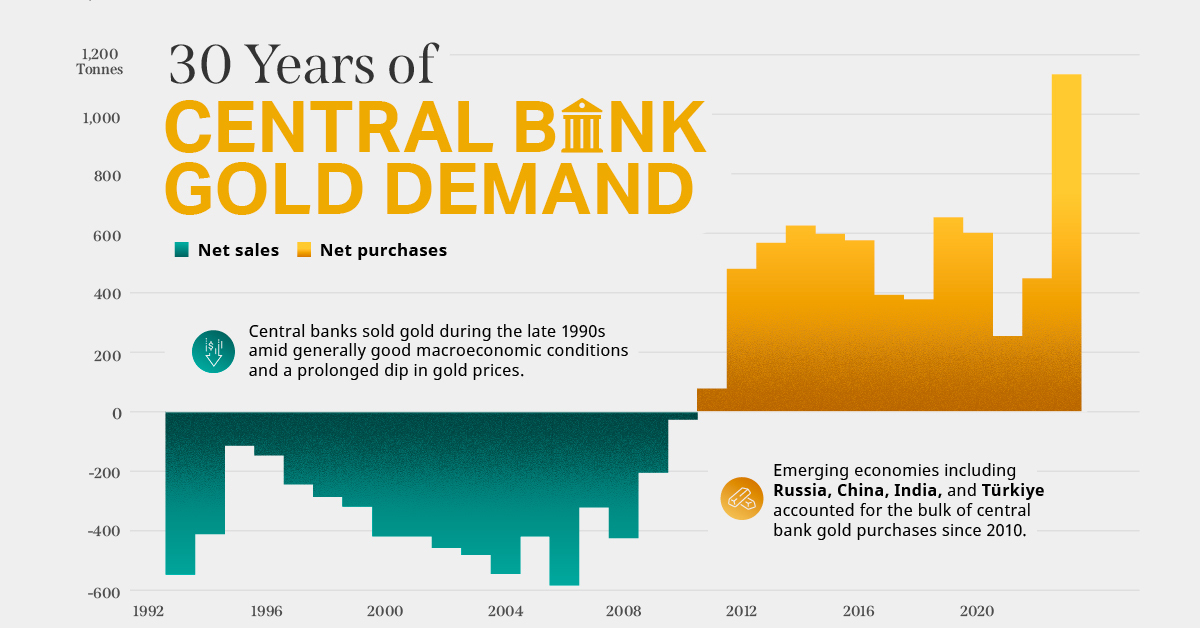

on Did you know that nearly one-fifth of all the gold ever mined is held by central banks? Besides investors and jewelry consumers, central banks are a major source of gold demand. In fact, in 2022, central banks snapped up gold at the fastest pace since 1967. However, the record gold purchases of 2022 are in stark contrast to the 1990s and early 2000s, when central banks were net sellers of gold. The above infographic uses data from the World Gold Council to show 30 years of central bank gold demand, highlighting how official attitudes toward gold have changed in the last 30 years.

Why Do Central Banks Buy Gold?

Gold plays an important role in the financial reserves of numerous nations. Here are three of the reasons why central banks hold gold:

Balancing foreign exchange reserves Central banks have long held gold as part of their reserves to manage risk from currency holdings and to promote stability during economic turmoil. Hedging against fiat currencies Gold offers a hedge against the eroding purchasing power of currencies (mainly the U.S. dollar) due to inflation. Diversifying portfolios Gold has an inverse correlation with the U.S. dollar. When the dollar falls in value, gold prices tend to rise, protecting central banks from volatility. The Switch from Selling to Buying In the 1990s and early 2000s, central banks were net sellers of gold. There were several reasons behind the selling, including good macroeconomic conditions and a downward trend in gold prices. Due to strong economic growth, gold’s safe-haven properties were less valuable, and low returns made it unattractive as an investment. Central bank attitudes toward gold started changing following the 1997 Asian financial crisis and then later, the 2007–08 financial crisis. Since 2010, central banks have been net buyers of gold on an annual basis. Here’s a look at the 10 largest official buyers of gold from the end of 1999 to end of 2021: Rank CountryAmount of Gold Bought (tonnes)% of All Buying #1🇷🇺 Russia 1,88828% #2🇨🇳 China 1,55223% #3🇹🇷 Türkiye 5418% #4🇮🇳 India 3956% #5🇰🇿 Kazakhstan 3455% #6🇺🇿 Uzbekistan 3115% #7🇸🇦 Saudi Arabia 1803% #8🇹🇭 Thailand 1682% #9🇵🇱 Poland1282% #10🇲🇽 Mexico 1152% Total5,62384% Source: IMF The top 10 official buyers of gold between end-1999 and end-2021 represent 84% of all the gold bought by central banks during this period. Russia and China—arguably the United States’ top geopolitical rivals—have been the largest gold buyers over the last two decades. Russia, in particular, accelerated its gold purchases after being hit by Western sanctions following its annexation of Crimea in 2014. Interestingly, the majority of nations on the above list are emerging economies. These countries have likely been stockpiling gold to hedge against financial and geopolitical risks affecting currencies, primarily the U.S. dollar. Meanwhile, European nations including Switzerland, France, Netherlands, and the UK were the largest sellers of gold between 1999 and 2021, under the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) framework. Which Central Banks Bought Gold in 2022? In 2022, central banks bought a record 1,136 tonnes of gold, worth around $70 billion. Country2022 Gold Purchases (tonnes)% of Total 🇹🇷 Türkiye14813% 🇨🇳 China 625% 🇪🇬 Egypt 474% 🇶🇦 Qatar333% 🇮🇶 Iraq 343% 🇮🇳 India 333% 🇦🇪 UAE 252% 🇰🇬 Kyrgyzstan 61% 🇹🇯 Tajikistan 40.4% 🇪🇨 Ecuador 30.3% 🌍 Unreported 74165% Total1,136100% Türkiye, experiencing 86% year-over-year inflation as of October 2022, was the largest buyer, adding 148 tonnes to its reserves. China continued its gold-buying spree with 62 tonnes added in the months of November and December, amid rising geopolitical tensions with the United States. Overall, emerging markets continued the trend that started in the 2000s, accounting for the bulk of gold purchases. Meanwhile, a significant two-thirds, or 741 tonnes of official gold purchases were unreported in 2022. According to analysts, unreported gold purchases are likely to have come from countries like China and Russia, who are looking to de-dollarize global trade to circumvent Western sanctions.

There were several reasons behind the selling, including good macroeconomic conditions and a downward trend in gold prices. Due to strong economic growth, gold’s safe-haven properties were less valuable, and low returns made it unattractive as an investment.

Central bank attitudes toward gold started changing following the 1997 Asian financial crisis and then later, the 2007–08 financial crisis. Since 2010, central banks have been net buyers of gold on an annual basis.

Here’s a look at the 10 largest official buyers of gold from the end of 1999 to end of 2021:

Source: IMF

The top 10 official buyers of gold between end-1999 and end-2021 represent 84% of all the gold bought by central banks during this period.

Russia and China—arguably the United States’ top geopolitical rivals—have been the largest gold buyers over the last two decades. Russia, in particular, accelerated its gold purchases after being hit by Western sanctions following its annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Interestingly, the majority of nations on the above list are emerging economies. These countries have likely been stockpiling gold to hedge against financial and geopolitical risks affecting currencies, primarily the U.S. dollar.

Meanwhile, European nations including Switzerland, France, Netherlands, and the UK were the largest sellers of gold between 1999 and 2021, under the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) framework.

Which Central Banks Bought Gold in 2022?

In 2022, central banks bought a record 1,136 tonnes of gold, worth around $70 billion. Türkiye, experiencing 86% year-over-year inflation as of October 2022, was the largest buyer, adding 148 tonnes to its reserves. China continued its gold-buying spree with 62 tonnes added in the months of November and December, amid rising geopolitical tensions with the United States. Overall, emerging markets continued the trend that started in the 2000s, accounting for the bulk of gold purchases. Meanwhile, a significant two-thirds, or 741 tonnes of official gold purchases were unreported in 2022. According to analysts, unreported gold purchases are likely to have come from countries like China and Russia, who are looking to de-dollarize global trade to circumvent Western sanctions.