During the latter part of the Industrial Revolution, Cambridge School economist Alfred Marshall looked at a particular question: why did certain industries concentrate in specific places? Marshall argued that the local concentration of industry created powerful economies promoting technical dynamism and innovation. This Chart of the Week highlights the spatial patterns and business relationships created at the urban scale. Marshall’s insights from the past help us understand present-day tech and media economies and the massive growth of urban regions.

The Logic of Concentration

Marshall observed that industrial concentration led to long-term tendencies such as increasing returns on capital and compounding regional advantages. The heart of this observation is that knowledge resides within the companies that make up a particular industry. Over time, these companies can accumulate even more information and direct the flow of new and innovative ideas. This creates local specialization and increasing profits, while also concentrating success, knowledge, and wealth into one key locale. He defined this pattern as a Marshallian Industrial District.

An Evolving Landscape: Four Patterns

Marshall’s work would later influence the work of Ann Markusen, who created a typology of three additional industrial patterns. The patterns identify what makes a city attractive or repellent to income-generating activities.

There are both benefits and problems—called “externalities”—associated with the spatial agglomeration of physical capital, companies, consumers, and workers:

Clusters for a Digital Age

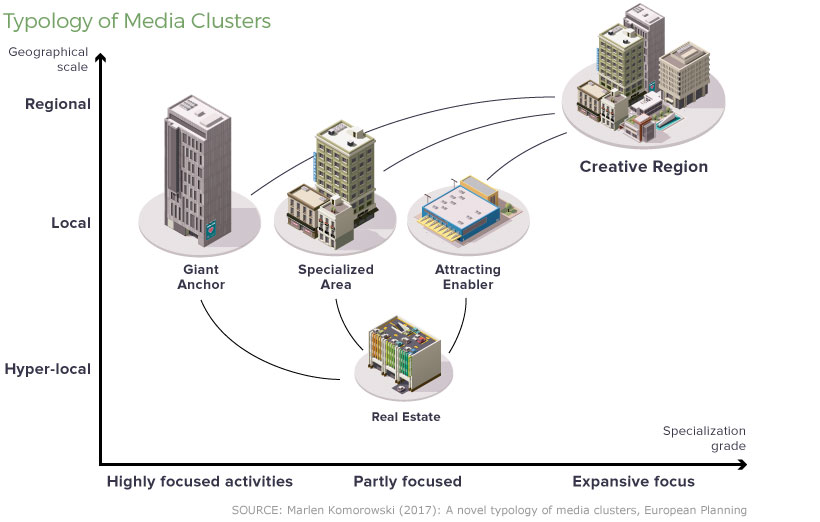

In the past, the physical constraints of an area defined the structure of cities. Now that so many companies are free from the shackles of producing physical goods, does geography still matter? Researcher Marlen Komorowski re-examined the concept of clustering with this question in mind. Here are five types of media clusters identified in her research.

Four rationales drive these patterns: agglomeration, urbanization, localization economies. and artificial formation.

The Shadow of the Industrial Revolution

Alfred Marshall made the argument that local concentration of industry can offer powerful economies and technical dynamism and innovation. We now see this pattern with the emergence of megacities that accrue the majority of the financial and knowledge returns. These megaregions set the perfect stage for dynamic economic exchanges between skilled labor, technology, and networks. What does your city look like? on Cities—settlements that are densely populated and self-administered—require many specific prerequisites to come into existence. The most crucial, especially for much of human history, is an abundance of food. Surplus food production leads to denser populations and allows for people to specialize in other skills that are not associated with basic human survival. But that also means that cities usually consume more primary goods than they produce. And their size requires a host of many other services—such as transport and sanitation—that are traditionally expensive to maintain. So maintaining large urban centers, and especially the world’s largest cities, was a monumental task. Mapper and history YouTuber Ollie Bye has visualized the seven largest cities in the world since 3,000 BCE. His video covers cities with a minimum population of 10,000 and hints at historical events which led to the establishment, growth, and eventual fall of cities.

The World’s Largest City Throughout History

With any historical data, accuracy is always a concern, and urban populations were rough and infrequent estimates up until the Industrial Revolution. Bye has used a variety of data sources—including the UN and many research papers—to create the dataset used in the video. In some places he also had to rely on his own estimates and criteria to keep the data reasonable and consistent:

In early history, some cities didn’t have given population estimates for long periods of time, and had to be equalized or estimated through other sources. For example, Babylon had a population estimate at 1,600 BCE (60,000) and at 1,200 BCE (75,000) but none in the 400 years between. Cities that only briefly climbed above a population of 10,000, or that would have made the largest cities ranking for only a couple of years (and based on uncertain estimates), were not included.

Here’s a look at the largest city starting from the year 3,000 BCE, with populations listed in millions during the last year of each city’s “reign.” Cities are also listed with the flags of current-day countries in the same location.

Ancient Cities in the Fertile Crescent

Considered the “cradle of civilization,” the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East was home to all seven of the largest cities in the world in 3,000 BCE. The Sumerian city of Uruk (modern-day Iraq), allegedly home to the legendary king Gilgamesh, topped the list with 40,000 people. It was followed by Memphis (Egypt) with 20,000 inhabitants. For the next 1,700 years, other Mesopotamian cities in modern-day Iraq and Syria held pole positions, growing steadily and shuffling between themselves as the largest. 2,250 BCE marked the first time a different Asian city—Mohenjo-Daro (modern-day Pakistan) from the Indus Valley Civilization—found a spot at #4 with 40,000 people. The table below is a quick snapshot of the seven largest cities in the world for from 3,000 BCE to 200 CE. Again, populations are listed in millions. It wasn’t until 1,250 BCE that the top two spots were taken by cities in different regions: Pi-Ramesses (Egypt) and Yin (China), both with more than 100,000 residents. Egyptian cities would continue to be the most populous for the next millennium—briefly interrupted by Carthage and Babylon—until the start of the Common Era. By 30 CE, Alexandria was the largest city in the world, but the top 10 had representatives from the Middle East, Northern Africa, and Asia.

All Roads Lead to Rome

One city in Europe meanwhile, was also beginning to see steady growth—Rome. It took until halfway through the 3rd century C.E. for Rome to become the most populous city, followed closely still by Alexandria (Egypt). Meanwhile in Iraq, Ctesiphon, the capital of the Sasanian empire was growing rapidly. Towards the end of the 3rd century, the Roman empire was divided into two, with Constantinople becoming the new capital for the Eastern half. Consequently, it had outgrown Rome by 353 and become the world’s most populous city, and for the next few centuries would reclaim this title time and time again.

The Largest Cities Reach 1 Million

In the 9th century, Baghdad became the first city to have 1 million residents (though historians also estimate Rome and the Chinese city of Chang’an may have achieved that figure earlier). It would be nearly nine centuries until a city had one million inhabitants again, and Baghdad’s reign didn’t last long. By the 10th century, Bian, the capital of the Northern Song dynasty in China, had become the largest city in the world, with Baghdad suffering from relocations and shifting political power to other cities in the region. From the 12th century onwards, Mongol invasions in the Middle East and Central Asia severely limited population growth in the region. European cities too were ravaged in the 14th century, but by plagues instead of marauders. For the next few hundred years, Cairo (Egypt), Hangzhou (China), and Vijayanagara (India) would top the list until Beijing took (and mostly held onto) the top spot through the 19th century.

Industrial Revolution and Rapid Urbanization

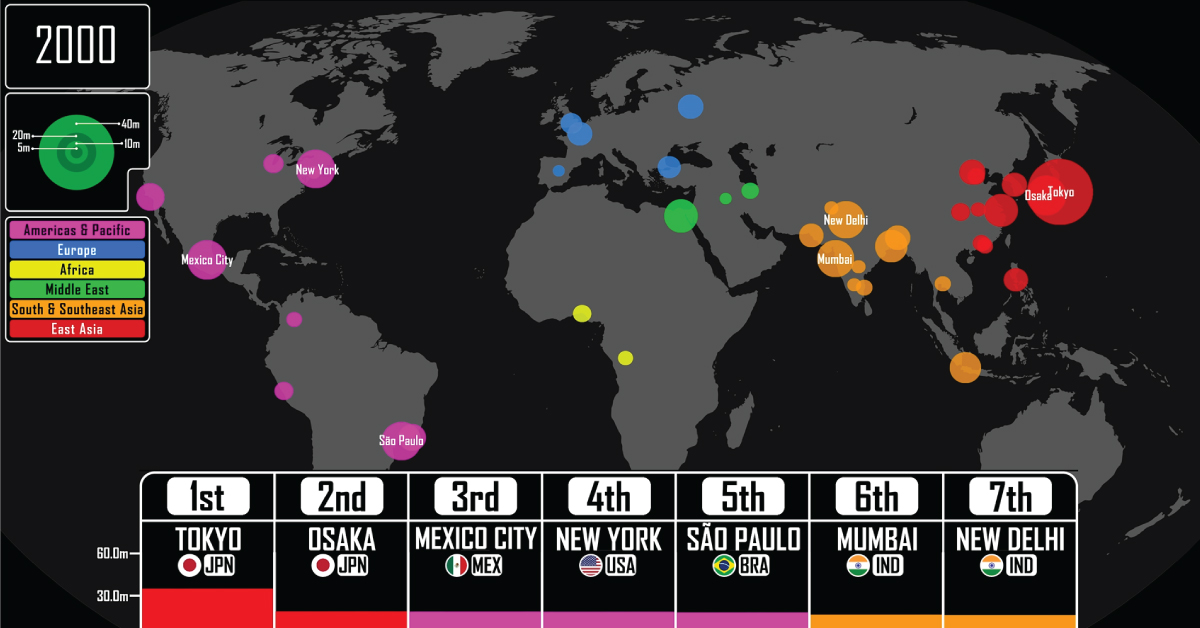

The start of the Industrial Revolution in the UK—spreading to the rest of Europe and later on the U.S.—led to hitherto unseen levels of urban population growth. Factories needed labor, which caused mass emigration from the rural countryside to urban centers of growth. In 1827, London passed Beijing to become the largest city in the world with 1.3 million residents. Over the next 100 years, its population increased nearly 7 times, remaining the most populous city until the end of World War I, by which time it was overtaken by New York. From 1920 to 2022, the world population quadrupled thanks to improvements in farming and healthcare, and cities saw rapid growth as well. The beginning of the 20st century saw the top 10 largest cities in the world in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. By the 21st century however, growth shifted away to other parts of the world and by 2021, the top seven had cities only from Asia and the Americas. Tokyo, which took the top spot in 1954, is the largest city in the world today with a population of 37 million (including the entire metropolitan area). It is followed by New Delhi with 31 million, but by 2028, the UN estimates that positions will switch on the leaderboard and New Delhi will overtake Tokyo.

What Does Population Growth Say About the Past (and Future)?

The rise and fall of cities through the sands of time can give us insight into the trajectory of civilization growth. As civilizations grow, become richer, and reach their zenith, so too do their cities blossom in tandem. For example, of the modern-day seven largest cities in the world, four of them belong to countries with the 10 largest economies in the world. Meanwhile, sudden falls in urban population point to turbulence—political instability, wars, natural disasters, or disease. Most recently Ukraine’s cities are seeing depopulation as residents flee conflict zones, raising the specter of a demographic crisis for the country should the war continue. Thus, tracking the size of urban population can help policymakers forecast future roadblocks to growth, especially when prioritizing sustainable growth for a country.