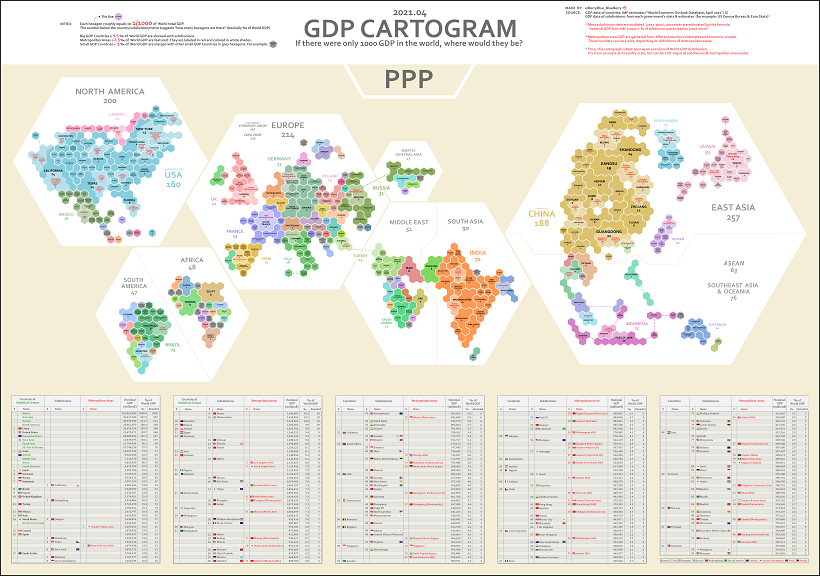

As a result, we don’t often get to see the nuances of the global economy, such as how much specific regions and metro areas contribute to global GDP. In these cartograms, global GDP has been normalized to a base number of 1,000 in order to show a more regional breakdown of economic activity. Created by Reddit user /BerryBlue_Blueberry, the two maps show the distribution in different ways: by nominal GDP and by GDP adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP).

Methodology

Before diving in, let us give you some context on how these maps were designed. Each hexagon on the two maps represents 0.1% of the world’s overall GDP. The number below each region, country or metropolitan area represents the number of hexagons covered by that entity. So in the nominal GDP map, the state of New York represents 20 hexagons (i.e. 2.0% of global GDP), while Munich’s metro area is 3 hexagons (0.3%). Countries are further broken down based on size. Countries that make up more than 0.95% of global GDP are broken down into subdivisions, while countries that are smaller than 0.1% of GDP are grouped together. Metro areas that account for over 0.25% of global GDP are featured. Finally, it should be noted that to account for some outdated subdivision participation data, the map creator calculated 2021 estimates for this using the formula: national GDP (2021) x % of subdivision participation (2017-2020).

Nominal vs. PPP

The above map is using nominal data, while the below map accounts for differences in purchasing power (PPP). Adjusting for PPP takes into account the relative value of currencies and purchasing power in countries around the world. For example, $100 (or its exchange equivalent in Indian rupees) is generally going to be able to buy more in India than it is in the United States. This is because goods and services are cheaper in India, meaning you can actually purchase more there for the same amount of money.

Anomalies in Global GDP Distribution

Breaking down global GDP distribution into cartograms highlights some interesting anomalies worth considering:

Inequality of GDP Distribution

The fact that certain countries generate most of the world’s economic output is reflected in the above cartograms, which resize countries or regions accordingly. Compared to wealthier nations, emerging economies still account for just a tiny sliver of the pie. India, for example, accounts for 3.2% of global GDP in nominal terms, even though it contains 17.8% of the world’s population. That’s why on the nominal map, India is about the same size as France, the United Kingdom, or Japan’s two largest metro areas (Tokyo and Osaka-Kobe)—but of course, these wealthier places have a far higher GDP per capita. on Last year, stock and bond returns tumbled after the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates at the fastest speed in 40 years. It was the first time in decades that both asset classes posted negative annual investment returns in tandem. Over four decades, this has happened 2.4% of the time across any 12-month rolling period. To look at how various stock and bond asset allocations have performed over history—and their broader correlations—the above graphic charts their best, worst, and average returns, using data from Vanguard.

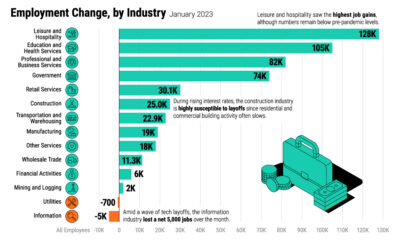

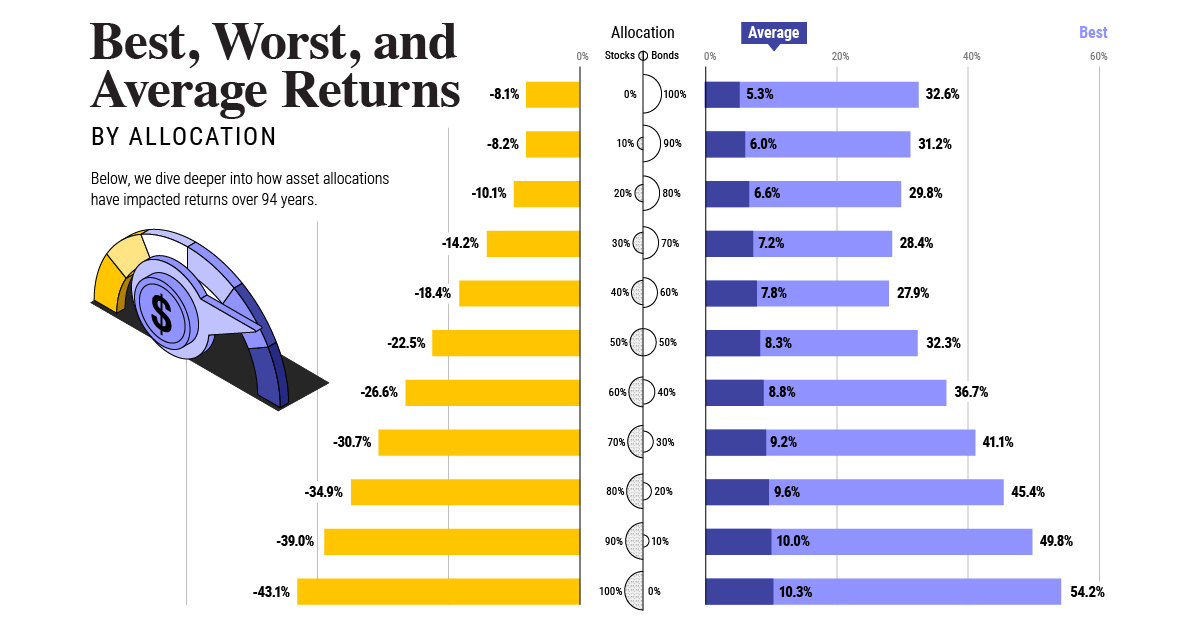

How Has Asset Allocation Impacted Returns?

Based on data between 1926 and 2019, the table below looks at the spectrum of market returns of different asset allocations:

We can see that a portfolio made entirely of stocks returned 10.3% on average, the highest across all asset allocations. Of course, this came with wider return variance, hitting an annual low of -43% and a high of 54%.

A traditional 60/40 portfolio—which has lost its luster in recent years as low interest rates have led to lower bond returns—saw an average historical return of 8.8%. As interest rates have climbed in recent years, this may widen its appeal once again as bond returns may rise.

Meanwhile, a 100% bond portfolio averaged 5.3% in annual returns over the period. Bonds typically serve as a hedge against portfolio losses thanks to their typically negative historical correlation to stocks.

A Closer Look at Historical Correlations

To understand how 2022 was an outlier in terms of asset correlations we can look at the graphic below:

The last time stocks and bonds moved together in a negative direction was in 1969. At the time, inflation was accelerating and the Fed was hiking interest rates to cool rising costs. In fact, historically, when inflation surges, stocks and bonds have often moved in similar directions. Underscoring this divergence is real interest rate volatility. When real interest rates are a driving force in the market, as we have seen in the last year, it hurts both stock and bond returns. This is because higher interest rates can reduce the future cash flows of these investments. Adding another layer is the level of risk appetite among investors. When the economic outlook is uncertain and interest rate volatility is high, investors are more likely to take risk off their portfolios and demand higher returns for taking on higher risk. This can push down equity and bond prices. On the other hand, if the economic outlook is positive, investors may be willing to take on more risk, in turn potentially boosting equity prices.

Current Investment Returns in Context

Today, financial markets are seeing sharp swings as the ripple effects of higher interest rates are sinking in. For investors, historical data provides insight on long-term asset allocation trends. Over the last century, cycles of high interest rates have come and gone. Both equity and bond investment returns have been resilient for investors who stay the course.