Oil is one of the world’s most important natural resources, playing a critical role in everything from transportation fuels to cosmetics. For this reason, many governments choose to nationalize their supply of oil. This gives them a greater degree of control over their oil reserves as well as access to additional revenue streams. In practice, nationalization often involves the creation of a national oil company to oversee the country’s energy operations. What are the world’s largest and most influential state-owned oil companies? Editor’s Note: This post and infographic are intended to provide a broad summary of the state-owned oil industry. Due to variations in reporting and available information, the companies named do not represent a comprehensive index.

State-Owned Oil Companies by Revenue

National oil companies are a major force in the global energy sector, controlling approximately three-quarters of the Earth’s oil reserves. As a result, many have found their place on the Fortune Global 500 list, a ranking of the world’s 500 largest companies by revenue. *Value of Iranian petroleum exports in 2019. Source: Fortune, Statista, OPEC China is home to the two largest companies from this list, Sinopec Group and China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). Both are involved in upstream and downstream oil operations, where upstream refers to exploration and extraction, and downstream refers to refining and distribution. It’s worth noting that many of these companies are listed on public stock markets—Sinopec, for example, trades on exchanges located in Shanghai, Hong Kong, New York, and London. Going public can be an effective strategy for these companies as it allows them to raise capital for new projects, while also ensuring their governments maintain control. In the case of Sinopec, 68% of shares are held by the Chinese government. Saudi Aramco was the latest national oil company to follow this strategy, putting up 1.5% of its business in a 2019 initial public offering (IPO). At roughly $8.53 per share, Aramco’s IPO raised $25.6 billion, making it one of the world’s largest IPOs in history.

Geopolitical Tensions

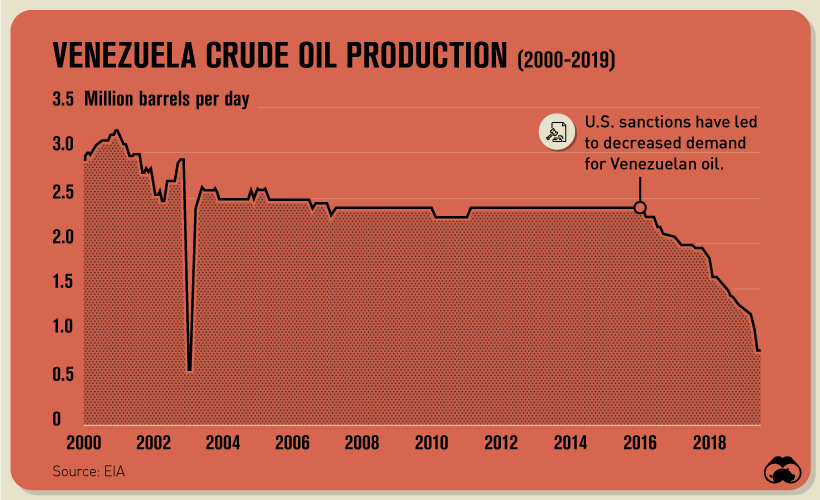

Because state-owned oil companies are directly tied to their governments, they can sometimes get caught in the crosshairs of geopolitical conflicts. The disputed presidency of Nicolás Maduro, for example, has resulted in the U.S. imposing sanctions against Venezuela’s government, central bank, and national oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). The pressure of these sanctions is proving to be particularly damaging, with PDVSA’s daily production in decline since 2016.

In a country for which oil comprises 95% of exports, Venezuela’s economic outlook is becoming increasingly dire. The final straw was drawn in August 2020 when the country’s last remaining oil rig suspended its operations. Other national oil companies at the receiving end of American sanctions include Russia’s Rosneft and Iran’s National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC). Rosneft was sanctioned by the U.S. in 2020 for facilitating Venezuelan oil exports, while NIOC was targeted for providing financial support to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, an entity designated as a foreign terrorist organization.

Climate Pressures

Like the rest of the fossil fuel industry, state-owned oil companies are highly exposed to the effects of climate change. This suggests that as time passes, many governments will need to find a balance between economic growth and environmental protection. These types of ultimatums may be an effective solution for driving climate action forward. In December 2020, Brazil’s national oil company, Petrobras, pledged a 25% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030. When asked about commitments further into the future, however, the company’s CEO appeared to be less enthusiastic. — Roberto Castello Branco, CEO, Petrobras With its 2030 pledge, Petrobras joins a growing collection of state-owned oil companies that have made public climate commitments. Another example is Malaysia’s Petronas, which in November 2020, announced its intention to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Petronas is wholly owned by the Malaysian government and is the country’s only entry on the Fortune Global 500.

Challenges Lie Ahead

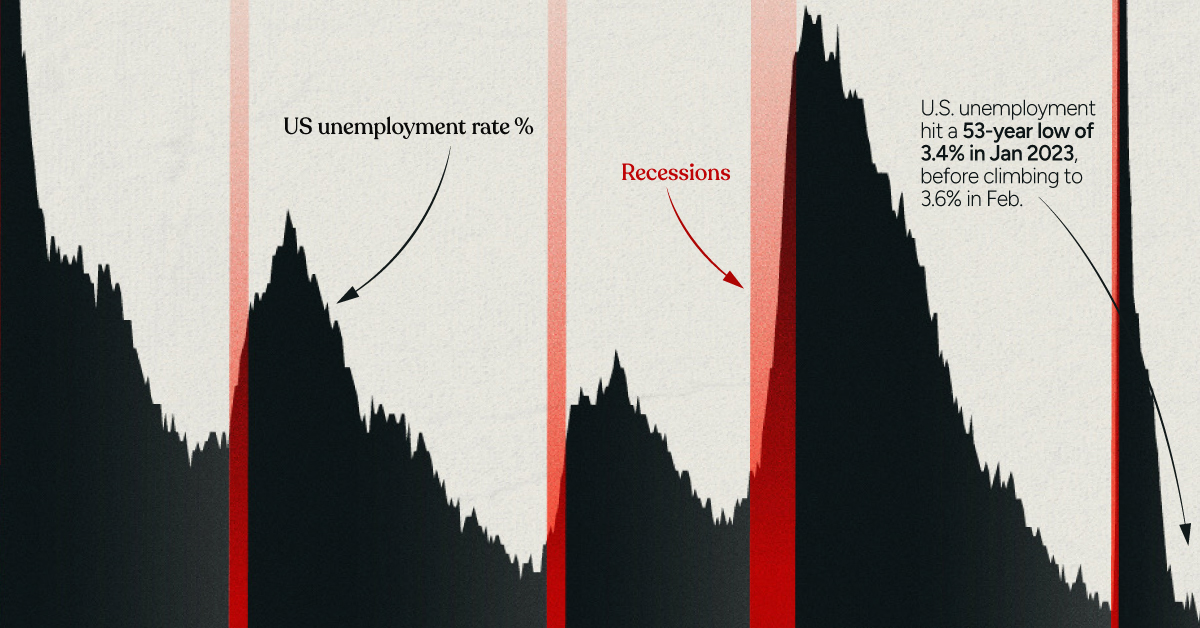

Between geopolitical conflicts, environmental concerns, and price fluctuations, state-owned oil companies are likely to face a much tougher environment in the decades to come. For Petronas, achieving its 2050 climate commitments will require significant investment in cleaner forms of energy. The company has been involved in numerous solar energy projects across Asia and has stated its interests in hydrogen fuels. Elsewhere, China’s national oil companies are dealing with a more near-term threat. In compliance with an executive order issued by the Trump Administration in November 2020, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) announced it would delist three of China’s state-run telecom companies. Analysts believe oil companies such as Sinopec could be delisted next, due to their ties with the Chinese military. on Both figures surpassed analyst expectations by a wide margin, and in January, the unemployment rate hit a 53-year low of 3.4%. With the recent release of February’s numbers, unemployment is now reported at a slightly higher 3.6%. A low unemployment rate is a classic sign of a strong economy. However, as this visualization shows, unemployment often reaches a cyclical low point right before a recession materializes.

Reasons for the Trend

In an interview regarding the January jobs data, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made a bold statement: While there’s nothing wrong with this assessment, the trend we’ve highlighted suggests that Yellen may need to backtrack in the near future. So why do recessions tend to begin after unemployment bottoms out?

The Economic Cycle

The economic cycle refers to the economy’s natural tendency to fluctuate between periods of growth and recession. This can be thought of similarly to the four seasons in a year. An economy expands (spring), reaches a peak (summer), begins to contract (fall), then hits a trough (winter). With this in mind, it’s reasonable to assume that a cyclical low in the unemployment rate (peak employment) is simply a sign that the economy has reached a high point.

Monetary Policy

During periods of low unemployment, employers may have a harder time finding workers. This forces them to offer higher wages, which can contribute to inflation. For context, consider the labor shortage that emerged following the COVID-19 pandemic. We can see that U.S. wage growth (represented by a three-month moving average) has climbed substantially, and has held above 6% since March 2022. The Federal Reserve, whose mandate is to ensure price stability, will take measures to prevent inflation from climbing too far. In practice, this involves raising interest rates, which makes borrowing more expensive and dampens economic activity. Companies are less likely to expand, reducing investment and cutting jobs. Consumers, on the other hand, reduce the amount of large purchases they make. Because of these reactions, some believe that aggressive rate hikes by the Fed can either cause a recession, or make them worse. This is supported by recent research, which found that since 1950, central banks have been unable to slow inflation without a recession occurring shortly after.

Politicians Clash With Economists

The Fed has raised interest rates at an unprecedented pace since March 2022 to combat high inflation. More recently, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell warned that interest rates could be raised even higher than originally expected if inflation continues above target. Senator Elizabeth Warren expressed concern that this would cost Americans their jobs, and ultimately, cause a recession. Powell remains committed to bringing down inflation, but with the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, some analysts believe there could be a pause coming in interest rate hikes. Editor’s note: just after publication of this article, it was confirmed that U.S. interest rates were hiked by 25 basis points (bps) by the Federal Reserve.