There are many considerations, such as:

Are the social handles and domain name available? Is there a competitor already using a similar name? Can people spell, pronounce, and remember the name? Are there cultural or symbolic interpretations that could be problematic?

The list goes on. These considerations are amplified when a company is already established, and even more difficult when your company serves billions of users around the globe. Facebook (the parent company, not the social network) has changed its name to Meta, and we’ll examine some probable reasons for the rebrand. But first we’ll look at historical corporate name changes in recent history, exploring the various motivations behind why a company might change its name. Below are some of the categories of rebranding that stand out the most.

Social Pressure

Societal perceptions can change fast, and companies do their best to anticipate these changes in advance. Or, if they don’t change in time, their hands might get forced.

As time goes on, companies with more overt negative externalities have come under pressure—particularly in the era of ESG investing. Social pressure was behind the name changes at Total and Philip Morris. In the case of the former, the switch to TotalEnergies was meant to signal the company’s shift beyond oil and gas to include renewable energy. In some cases, the reason why companies change their name is more subtle. GMAC (General Motors Acceptance Corporation) didn’t want to be associated with subprime lending and the subsequent multi-billion dollar bailout from the U.S. government, and a name change was one way of starting with a “clean slate”. The financial services company rebranded to Ally in 2010.

Hitting the Reset Button

Brands can become unpopular over time because of scandals, a decline in quality, or countless other reasons. When this happens, a name change can be a way of getting customers to shed those old, negative connotations.

Internet and TV providers rank dead last in customer satisfaction ratings, so it’s no surprise that many have changed their names in recent years.

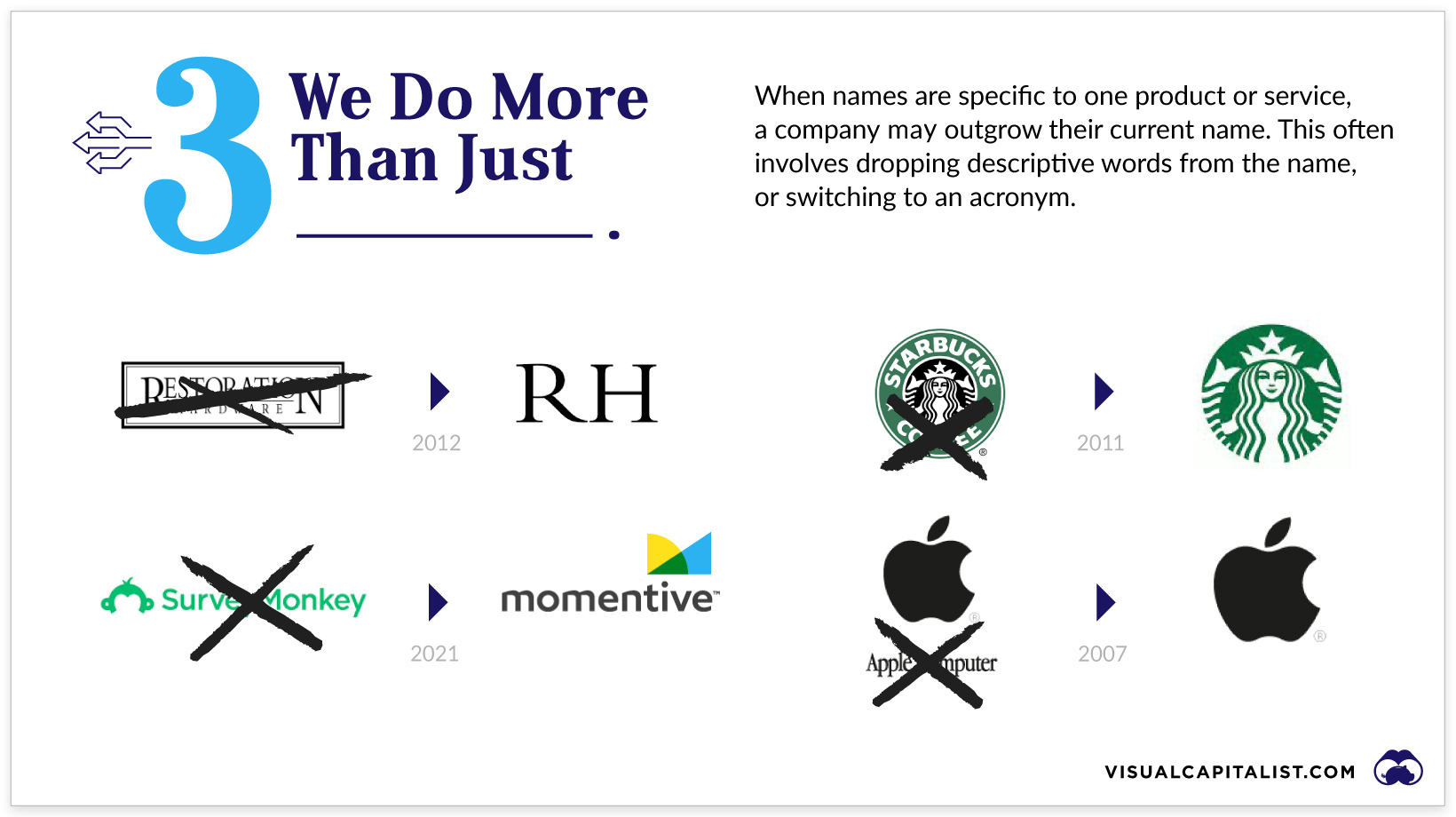

We Do More

This is a very common scenario, particularly as companies go through a rapid expansion or find success with new product offerings. After a period of sustained growth and change, a company may find that the current name is too limiting or no longer accurately reflects what the company has become.

Both Apple and Starbucks have simplified their company names over the years. The former dropped “Computers” from its name in 2007, and Starbucks dropped “Coffee” from its name in 2011. In both these cases, the name change meant disassociating the company with what initially made them successful, but in both cases it was a gamble that paid off. One of the biggest name changes in recent years is the switch from Google to Alphabet. This name change signaled the company’s desire to expand beyond internet search and advertising. Square also found itself in a similar situation. The “Square” brand had become synonymous with its commerce solutions, so the parent company became Block to help the company signal a shift into other areas of business.

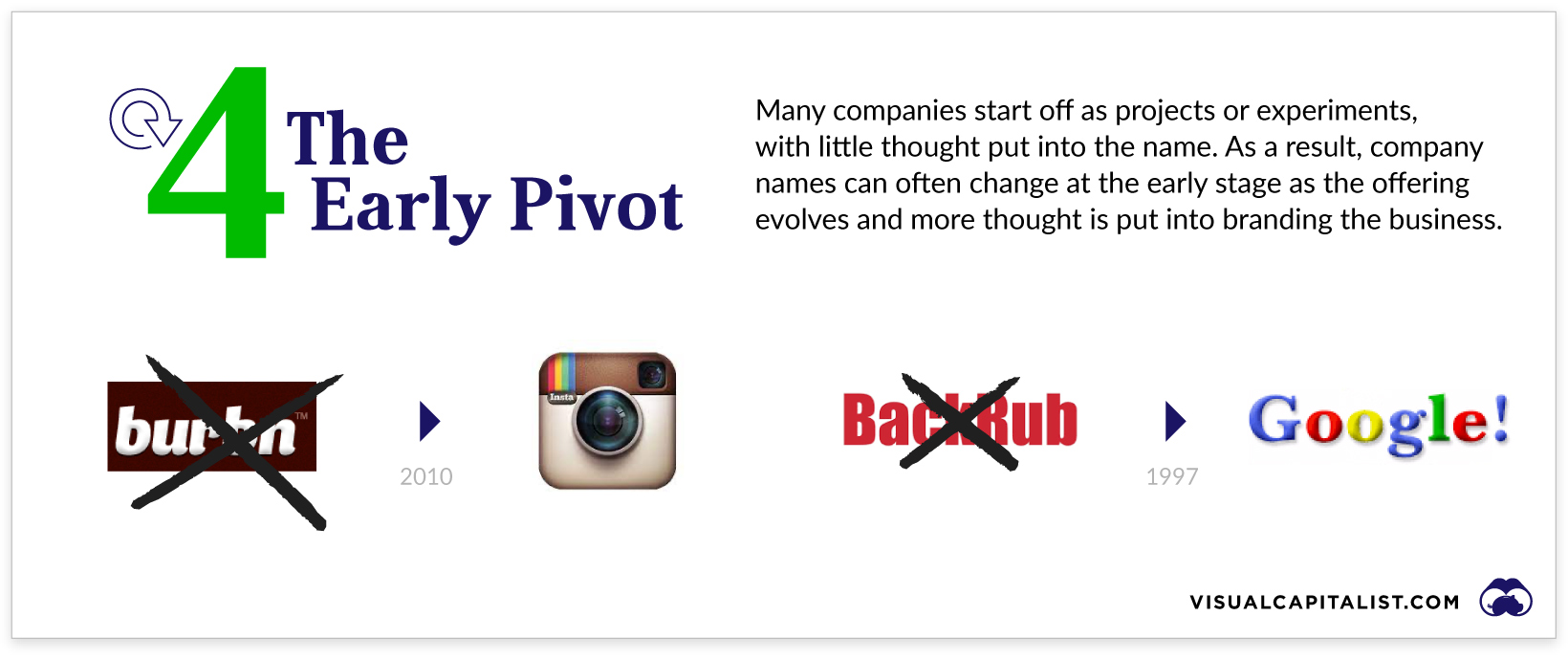

The Start-Up Name Pivot

Another very common name change scenario is the early-stage name change.

In the world of music, there’s speculation that limited melodies and subconscious plagiarism will make creating new music increasingly difficult in the future. Similarly, there are millions of companies in the world and only so many short and snappy names. (That’s how we end up with companies called Quibi.) Many of the popular digital services we use today started with very different names. The Google we know today was once called Backrub. Instagram began life as Bourbn, and Twitter began life as “Twittr” before finding a spare E in the scrabble pile.

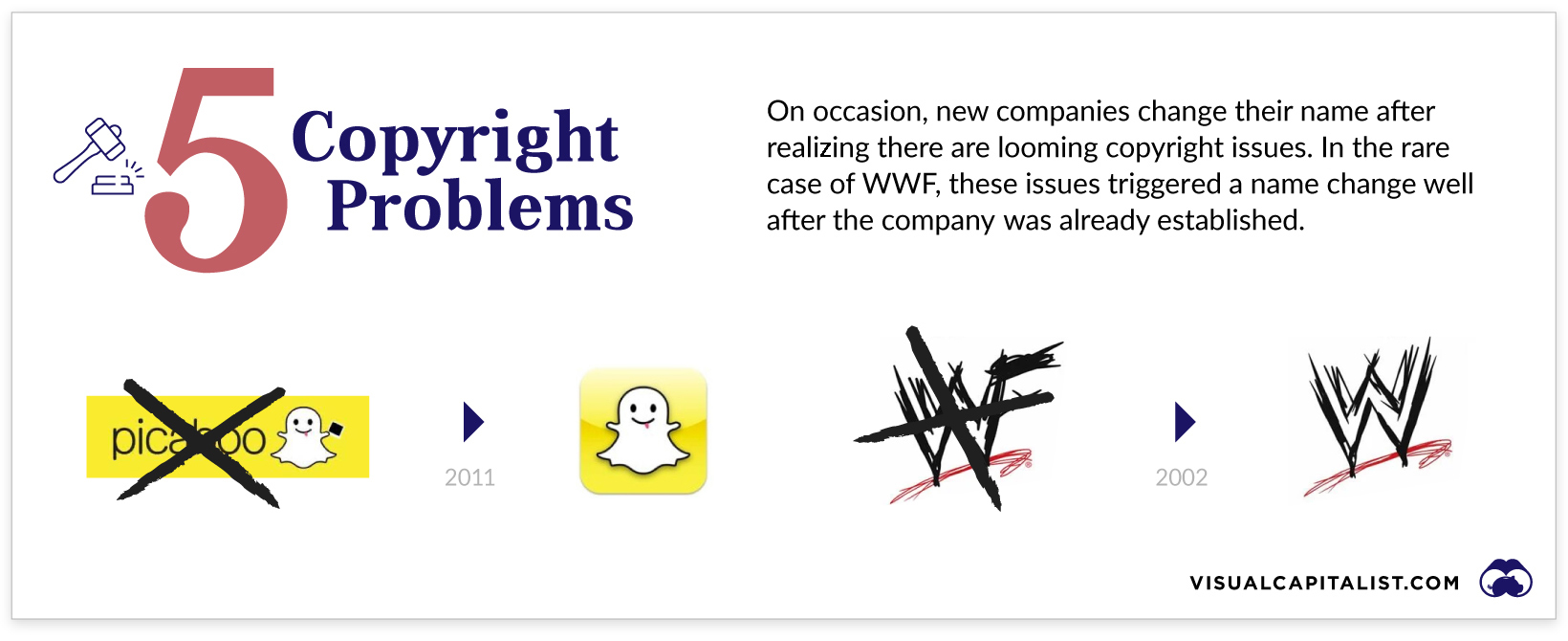

Trademark Problems

As mentioned above, many companies start out as speculative experiments or passion projects, when a viable, well-vetted name isn’t high on the priority list. As a result, new companies can run into trademark problems.

This was the case when Picaboo, the precursor of Snapchat, was forced to change their name in 2011. The existing Picaboo—a photobook company—was not thrilled to share a name with an app that was primarily associated with sexting at the time. The fight over the name WWF was a more unique scenario. In 1994, the World Wildlife Fund and the World Wrestling Federation had a mutual agreement that the latter would stop using the initials internationally, except for fleeting uses such as “WWF champion”. In the end though, the agreement was largely ignored, and the issue became a sticking point when the wrestling company registered wwf.com. Eventually, the company rebranded as WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment) after losing a lawsuit.

Course Correction

To err is human, and rebranding exercises don’t always hit the mark. When a name change is universally panned or, perhaps worse, not relevant, it’s time to course correct.

Tribune Publishing was forced to backtrack after their name change to Tronc in 2016. The widely-panned name, which was stylized in all lower case, was seen as a clumsy attempt to become a digital-first publisher.

Why Is Facebook Changing Its Name?

Facebook undertook this name change for a number of reasons, but chief among them is that the brand is irrevocably associated with scandals, negative externalities, and Mark Zuckerberg. Even before the most recent outage and whistle-blowing scandal, Facebook was already the least-trusted tech company by a long shot. Mark Zuckerberg was once the most admired CEO in Silicon Valley, but has since fallen from grace. It’s easy to focus on the negative triggers for the impending name change, but there is some substance behind the change as well. For one, Facebook recognizes that privacy issues have put their primary source of revenue at risk. The company’s ad-driven model built upon its users’ data is coming under increasing scrutiny with each passing year. As well, there is substance behind the metaverse hype. Facebook first signaled their ambitions in 2014, when it acquired the virtual reality headset maker Oculus. A sizable portion of the company’s workforce is already working on making the metaverse concept a reality, and there are plans to hire 10,000 more people in Europe over the next five years. It remains to be seen whether this immense gamble pays off, but for the near future, Zuckerberg and Facebook’s investors will be keeping a close eye on how the media and public react to the new Meta name and how the transition plays out. After all, there are billions of dollars at stake. on But fast forward to the end of last week, and SVB was shuttered by regulators after a panic-induced bank run. So, how exactly did this happen? We dig in below.

Road to a Bank Run

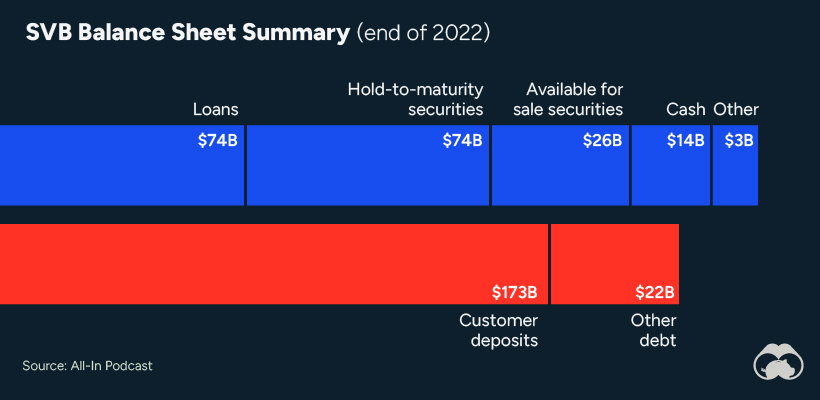

SVB and its customers generally thrived during the low interest rate era, but as rates rose, SVB found itself more exposed to risk than a typical bank. Even so, at the end of 2022, the bank’s balance sheet showed no cause for alarm.

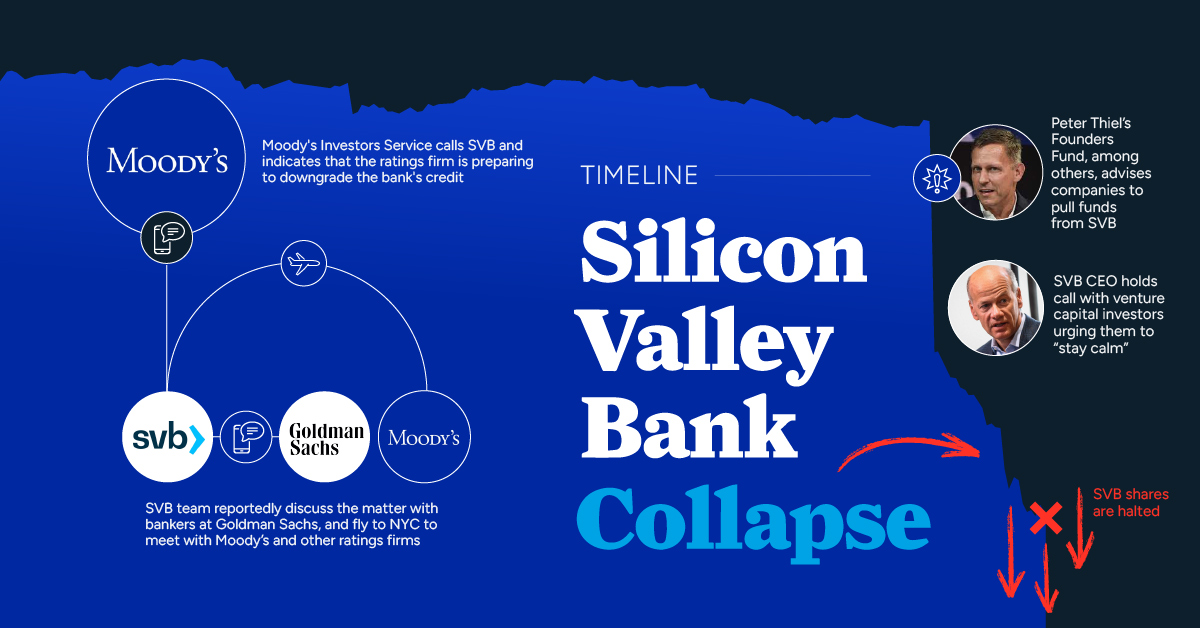

As well, the bank was viewed positively in a number of places. Most Wall Street analyst ratings were overwhelmingly positive on the bank’s stock, and Forbes had just added the bank to its Financial All-Stars list. Outward signs of trouble emerged on Wednesday, March 8th, when SVB surprised investors with news that the bank needed to raise more than $2 billion to shore up its balance sheet. The reaction from prominent venture capitalists was not positive, with Coatue Management, Union Square Ventures, and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund moving to limit exposure to the 40-year-old bank. The influence of these firms is believed to have added fuel to the fire, and a bank run ensued. Also influencing decision making was the fact that SVB had the highest percentage of uninsured domestic deposits of all big banks. These totaled nearly $152 billion, or about 97% of all deposits. By the end of the day, customers had tried to withdraw $42 billion in deposits.

What Triggered the SVB Collapse?

While the collapse of SVB took place over the course of 44 hours, its roots trace back to the early pandemic years. In 2021, U.S. venture capital-backed companies raised a record $330 billion—double the amount seen in 2020. At the time, interest rates were at rock-bottom levels to help buoy the economy. Matt Levine sums up the situation well: “When interest rates are low everywhere, a dollar in 20 years is about as good as a dollar today, so a startup whose business model is “we will lose money for a decade building artificial intelligence, and then rake in lots of money in the far future” sounds pretty good. When interest rates are higher, a dollar today is better than a dollar tomorrow, so investors want cash flows. When interest rates were low for a long time, and suddenly become high, all the money that was rushing to your customers is suddenly cut off.” Source: Pitchbook Why is this important? During this time, SVB received billions of dollars from these venture-backed clients. In one year alone, their deposits increased 100%. They took these funds and invested them in longer-term bonds. As a result, this created a dangerous trap as the company expected rates would remain low. During this time, SVB invested in bonds at the top of the market. As interest rates rose higher and bond prices declined, SVB started taking major losses on their long-term bond holdings.

Losses Fueling a Liquidity Crunch

When SVB reported its fourth quarter results in early 2023, Moody’s Investor Service, a credit rating agency took notice. In early March, it said that SVB was at high risk for a downgrade due to its significant unrealized losses. In response, SVB looked to sell $2 billion of its investments at a loss to help boost liquidity for its struggling balance sheet. Soon, more hedge funds and venture investors realized SVB could be on thin ice. Depositors withdrew funds in droves, spurring a liquidity squeeze and prompting California regulators and the FDIC to step in and shut down the bank.

What Happens Now?

While much of SVB’s activity was focused on the tech sector, the bank’s shocking collapse has rattled a financial sector that is already on edge.

The four biggest U.S. banks lost a combined $52 billion the day before the SVB collapse. On Friday, other banking stocks saw double-digit drops, including Signature Bank (-23%), First Republic (-15%), and Silvergate Capital (-11%).

Source: Morningstar Direct. *Represents March 9 data, trading halted on March 10.

When the dust settles, it’s hard to predict the ripple effects that will emerge from this dramatic event. For investors, the Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen announced confidence in the banking system remaining resilient, noting that regulators have the proper tools in response to the issue.

But others have seen trouble brewing as far back as 2020 (or earlier) when commercial banking assets were skyrocketing and banks were buying bonds when rates were low.