Over the last decade, the prospect of mass automation has seemingly shifted from a vague possibility to an inescapable reality. While it’s still incredibly difficult to estimate the ultimate impact of automation and AI on the economy, the picture is starting to become a bit clearer as projections begin to converge. Today’s infographic comes to us from Raconteur, and it highlights seven different charts that show us how automation is shaping the world – and in particular, the future outlook for manufacturing jobs.

The Age of Automation

The precise details are up to debate, but here are a few key areas that many experts agree on with respect to the coming age of automation: Half of manufacturing hours worked today are spent on manual jobs.

In an analysis of North American and European manufacturing jobs, it was found that roughly 48% of hours primarily relied on the use of manual or physical labor. By the year 2030, it’s estimated that only 35% of time will be spent on such routine work.

Automation’s impact will be felt by the mid-2020s.

According to a recent report from PwC, the impact on OECD jobs will start to be felt in the mid-2020s. By 2025, for example, it’s projected that 10-15% of jobs in three sectors (manufacturing, transportation and storage, and wholesales and retail trade) will have high potential for automation. By 2035, the range of jobs with high automation potential will be closer to 35-50% for those sectors.

Industrial robot prices are decreasing.

Industrial robot sales are sky high, mainly the result of falling industry costs. This trend is expected to continue, with the cost of robots falling by 65% between 2015 and 2025. With the cost of labor generally rising, this makes it more difficult to keep low-skilled jobs.

Technology simultaneously creates jobs, but how many?

One bright spot is that automation and AI will also create jobs, likely in functions that are difficult for us to conceive of today. Historically, technology has created more jobs than it has destroyed. AI alone is expected to have an economic impact of $15.7 trillion by 2030.

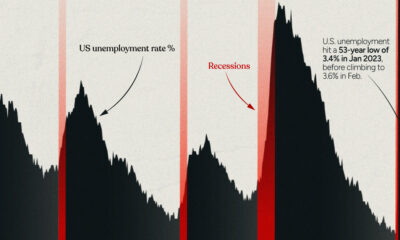

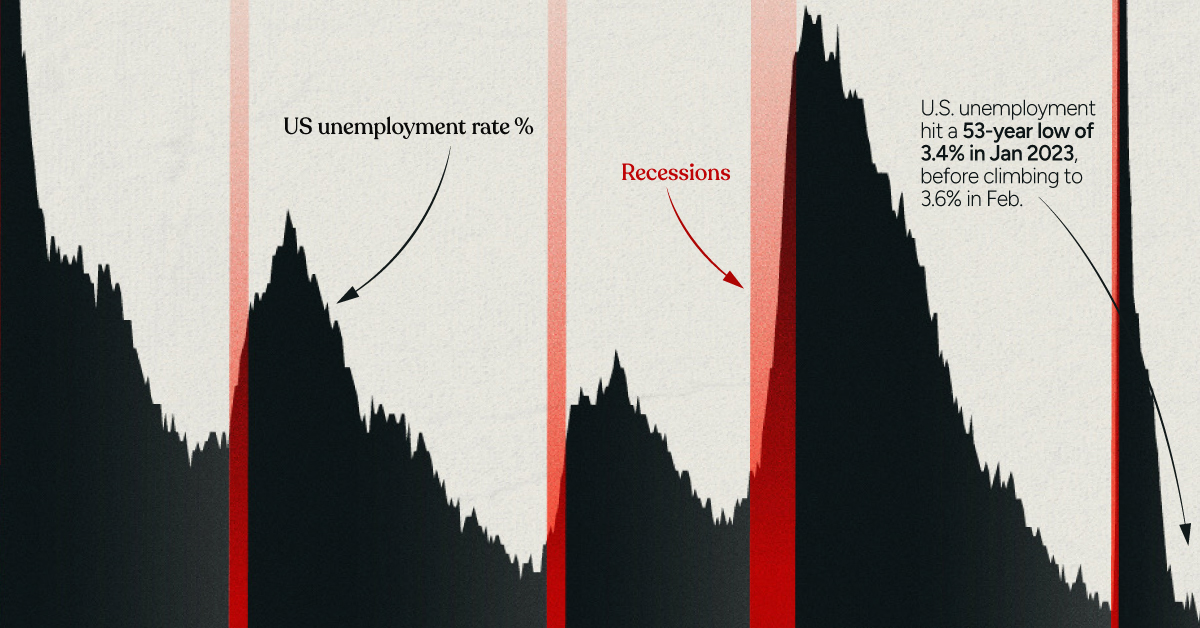

Unfortunately, although experts agree that jobs will be created by these technologies, they disagree considerably on how many. This important discrepancy is likely the biggest x-factor in determining the ultimate impact that these technologies will have in the coming years, especially on the workforce. on Both figures surpassed analyst expectations by a wide margin, and in January, the unemployment rate hit a 53-year low of 3.4%. With the recent release of February’s numbers, unemployment is now reported at a slightly higher 3.6%. A low unemployment rate is a classic sign of a strong economy. However, as this visualization shows, unemployment often reaches a cyclical low point right before a recession materializes.

Reasons for the Trend

In an interview regarding the January jobs data, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made a bold statement: While there’s nothing wrong with this assessment, the trend we’ve highlighted suggests that Yellen may need to backtrack in the near future. So why do recessions tend to begin after unemployment bottoms out?

The Economic Cycle

The economic cycle refers to the economy’s natural tendency to fluctuate between periods of growth and recession. This can be thought of similarly to the four seasons in a year. An economy expands (spring), reaches a peak (summer), begins to contract (fall), then hits a trough (winter). With this in mind, it’s reasonable to assume that a cyclical low in the unemployment rate (peak employment) is simply a sign that the economy has reached a high point.

Monetary Policy

During periods of low unemployment, employers may have a harder time finding workers. This forces them to offer higher wages, which can contribute to inflation. For context, consider the labor shortage that emerged following the COVID-19 pandemic. We can see that U.S. wage growth (represented by a three-month moving average) has climbed substantially, and has held above 6% since March 2022. The Federal Reserve, whose mandate is to ensure price stability, will take measures to prevent inflation from climbing too far. In practice, this involves raising interest rates, which makes borrowing more expensive and dampens economic activity. Companies are less likely to expand, reducing investment and cutting jobs. Consumers, on the other hand, reduce the amount of large purchases they make. Because of these reactions, some believe that aggressive rate hikes by the Fed can either cause a recession, or make them worse. This is supported by recent research, which found that since 1950, central banks have been unable to slow inflation without a recession occurring shortly after.

Politicians Clash With Economists

The Fed has raised interest rates at an unprecedented pace since March 2022 to combat high inflation. More recently, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell warned that interest rates could be raised even higher than originally expected if inflation continues above target. Senator Elizabeth Warren expressed concern that this would cost Americans their jobs, and ultimately, cause a recession. Powell remains committed to bringing down inflation, but with the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, some analysts believe there could be a pause coming in interest rate hikes. Editor’s note: just after publication of this article, it was confirmed that U.S. interest rates were hiked by 25 basis points (bps) by the Federal Reserve.