War, homicide, terrorism, suicide, and sexual assault can be found across the world in various degrees. While certain types of violence can incur costs that result in personal traumas, violence can also create significant economic disruptions. In today’s Chart of the Week, we visualize data estimates from the Global Peace Index 2019 on the global cost of violence, and its geographical spread.

How is Violence Linked to the Economy?

The Global Peace Index calculates the total cost of violence using purchasing power parity (PPP) by considering three factors:

Direct costs: Immediate consequences to the victims, perpetrators and the government Indirect costs: Delayed economic losses following the violent event, including the after-effects of trauma experienced by the victim Multiplier effect: Calculates the additional economic activity that would have accrued if the direct costs of violence had been avoided.

Between 2012-2017, the cost of violence increased by 11% to $14.6 trillion—mainly due to rising violence in Syria, Libya, Yemen, and other parts of the Middle East and North Africa. In 2018, the total cost of violence decreased for the first time in six years to $14.1 trillion. That’s the equivalent of 11.2% of global GDP (PPP), or $1,853 for every person. In this one year, the $475 billion saved from decreased violence costs was largely due to lower levels of armed conflict in Syria, Ukraine, and Colombia.

The Top 10 Worst Affected Countries

It comes as no surprise that countries affected by conflict incur the greatest costs due to a higher than average death toll, and sizable military expenditures. Here are the countries with the highest cost of violence according to the report: Since 2017, Venezuela has climbed the ranking and now sits in the top 10, due to continuing political repression and a spiraling economy as a result of hyperinflation.

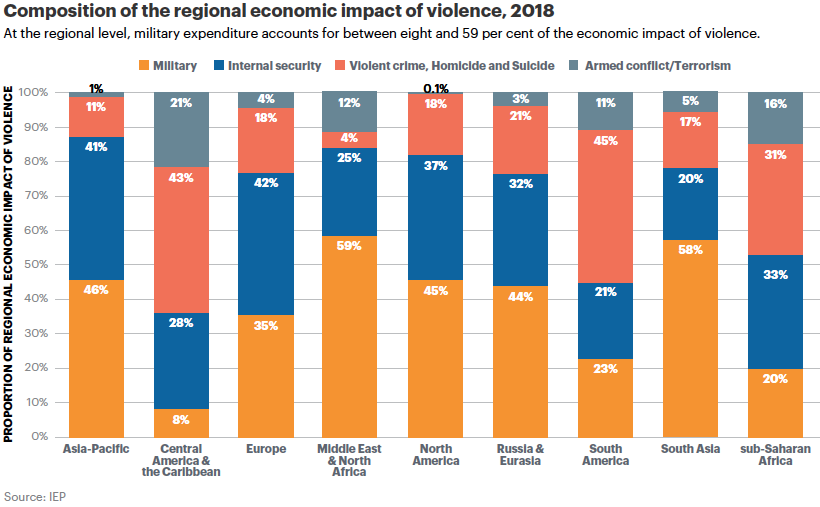

The Global Composition of Violence

Government spending on military comprises 40% of the global total, or $5.7 trillion in constant purchasing power parity (PPP). Naturally, the types of violence costs vary by region, and the most noticeable difference is in military expenditure. It represents 59% of Middle East and North Africa’s violence costs—but only 8% for Central America and the Caribbean.

Interestingly, the Middle East and North Africa boast the lowest levels of violent crime, homicide, and suicide, representing only 4% of the total, compared to South America’s 45%.

Keeping the Peace

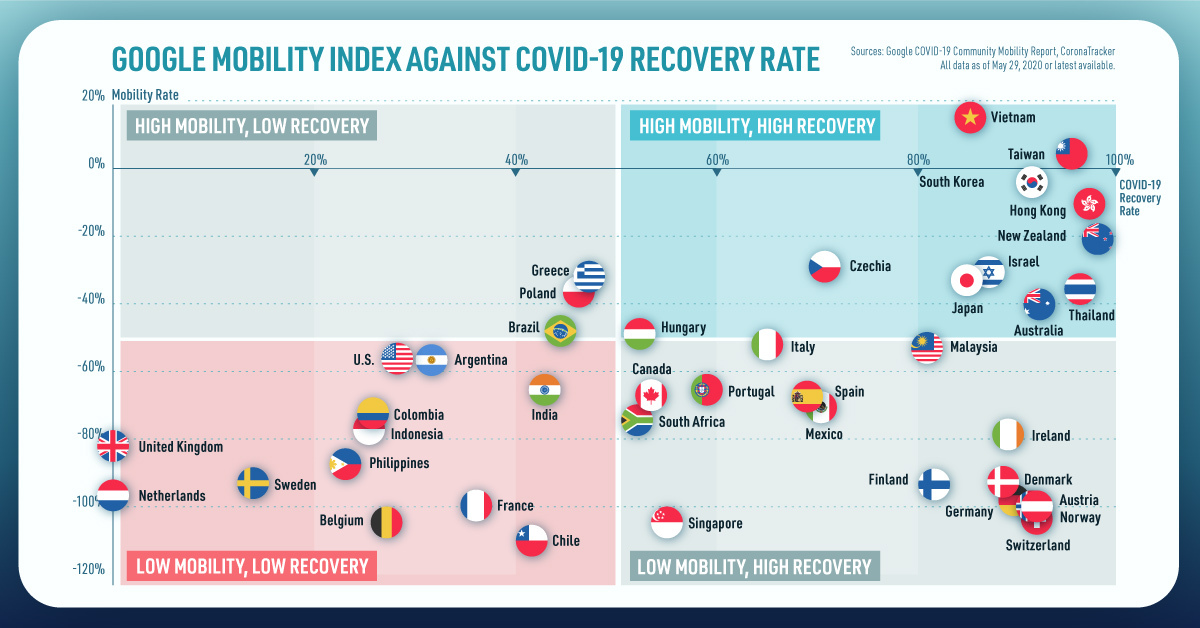

Despite today’s chart painting a picture of the world as a dangerous place, it is worth noting that there are two sides to this story. Of the 163 countries ranked in the index, 86 countries improved their peace score in the last year, with Iceland retaining its number one position for over a decade. In fact, the country has not had any gun murders since the Global Peace Index began in 2007. Is the recent drop in costs of violence a sign that we are moving towards a more peaceful planet, or just a blip on the radar? on Today’s chart measures the extent to which 41 major economies are reopening, by plotting two metrics for each country: the mobility rate and the COVID-19 recovery rate: Data for the first measure comes from Google’s COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports, which relies on aggregated, anonymous location history data from individuals. Note that China does not show up in the graphic as the government bans Google services. COVID-19 recovery rates rely on values from CoronaTracker, using aggregated information from multiple global and governmental databases such as WHO and CDC.

Reopening Economies, One Step at a Time

In general, the higher the mobility rate, the more economic activity this signifies. In most cases, mobility rate also correlates with a higher rate of recovered people in the population. Here’s how these countries fare based on the above metrics. Mobility data as of May 21, 2020 (Latest available). COVID-19 case data as of May 29, 2020. In the main scatterplot visualization, we’ve taken things a step further, assigning these countries into four distinct quadrants:

1. High Mobility, High Recovery

High recovery rates are resulting in lifted restrictions for countries in this quadrant, and people are steadily returning to work. New Zealand has earned praise for its early and effective pandemic response, allowing it to curtail the total number of cases. This has resulted in a 98% recovery rate, the highest of all countries. After almost 50 days of lockdown, the government is recommending a flexible four-day work week to boost the economy back up.

2. High Mobility, Low Recovery

Despite low COVID-19 related recoveries, mobility rates of countries in this quadrant remain higher than average. Some countries have loosened lockdown measures, while others did not have strict measures in place to begin with. Brazil is an interesting case study to consider here. After deferring lockdown decisions to state and local levels, the country is now averaging the highest number of daily cases out of any country. On May 28th, for example, the country had 24,151 new cases and 1,067 new deaths.

3. Low Mobility, High Recovery

Countries in this quadrant are playing it safe, and holding off on reopening their economies until the population has fully recovered. Italy, the once-epicenter for the crisis in Europe is understandably wary of cases rising back up to critical levels. As a result, it has opted to keep its activity to a minimum to try and boost the 65% recovery rate, even as it slowly emerges from over 10 weeks of lockdown.

4. Low Mobility, Low Recovery

Last but not least, people in these countries are cautiously remaining indoors as their governments continue to work on crisis response. With a low 0.05% recovery rate, the United Kingdom has no immediate plans to reopen. A two-week lag time in reporting discharged patients from NHS services may also be contributing to this low number. Although new cases are leveling off, the country has the highest coronavirus-caused death toll across Europe. The U.S. also sits in this quadrant with over 1.7 million cases and counting. Recently, some states have opted to ease restrictions on social and business activity, which could potentially result in case numbers climbing back up. Over in Sweden, a controversial herd immunity strategy meant that the country continued business as usual amid the rest of Europe’s heightened regulations. Sweden’s COVID-19 recovery rate sits at only 13.9%, and the country’s -93% mobility rate implies that people have been taking their own precautions.

COVID-19’s Impact on the Future

It’s important to note that a “second wave” of new cases could upend plans to reopen economies. As countries reckon with these competing risks of health and economic activity, there is no clear answer around the right path to take. COVID-19 is a catalyst for an entirely different future, but interestingly, it’s one that has been in the works for a while. —Carmen Reinhart, incoming Chief Economist for the World Bank Will there be any chance of returning to “normal” as we know it?